A Guide to State Permitting

Getting into the nitty-gritty

Welcome Back!

Apologies for the hiatus, the FAI State Permitting effort has been running at full tilt. We have the new edition of the State Permitting Playbook, expanding our coverage to 49 states; an expansion pack focused on what states can do to improve the prospects of nuclear energy in their states; and, thanks to the inimitable Daniel King, a second expansion pack targeting behind-the-meter reforms for states grappling with data centre expansion.

Good at Permitting?

As part of these projects, I have been thinking a great deal about what we mean when we say a state is good at permitting. Good at permitting how? Does the state intrude minimally? Does the state balance environmental and development considerations? Does nothing that would cause an environmental harm ever get built?

If you’re at all interested in the permitting debate—at the state or federal level—you likely have views that adhere to one of the three categories above. But, at the risk of stating the obvious, these are three very different definitions of being good at permitting, with very different yardsticks for measuring success. The first is about providing a minimum level of protection for the worst environmental harms, with a strong focus on development. The second is a middle ground, focused on considering the balance of the upsides and downsides—accepting some harm for some development. The last is skeptical of our ability to perform analysis at all, particularly when there are long-tail risks of ecosystem collapse.

Personally, I fall firmly into the first camp. I believe that humanity’s creations are at least as good and worthy of respect as nature’s, and that nature is more resilient than people give it credit for. With exceptions for areas where the human cost is clear, such as air pollution, or where nature is at its most beautiful, such as the parks system, I believe the state should support new industrial development—not stymie it. However, with that said, a great deal of the furor around permitting is about tradeoffs which do not clearly need to be made. There are other dimensions where permitting can be improved beyond how extensive the legal protections are. But before diving into those waters, first, some concessions.

Allowing Variance

Despite my personal proclivities, some states should obviously have strong environmental protections. For all of the flack the state gets for its protections stifling development, California remains one of the most beautiful and ecologically diverse areas on the planet. From the stark majesty of the Sierra Nevadas to the ancient splendor of the redwood forests to the silent desolation of the Mojave Desert, nearly every inch of the state is speckled with natural wonder.

Compare this with West Texas. I have personally driven through West Texas no fewer than a dozen times. If asked under pain of death, I could not come up with a single notable feature. Perhaps the pumpjacks. Not exactly natural beauty. Quite obviously, these two places should not have the same standard of environmental protection. Whether the baseline is more or less protective, the variance between these places can—and should—remain high.

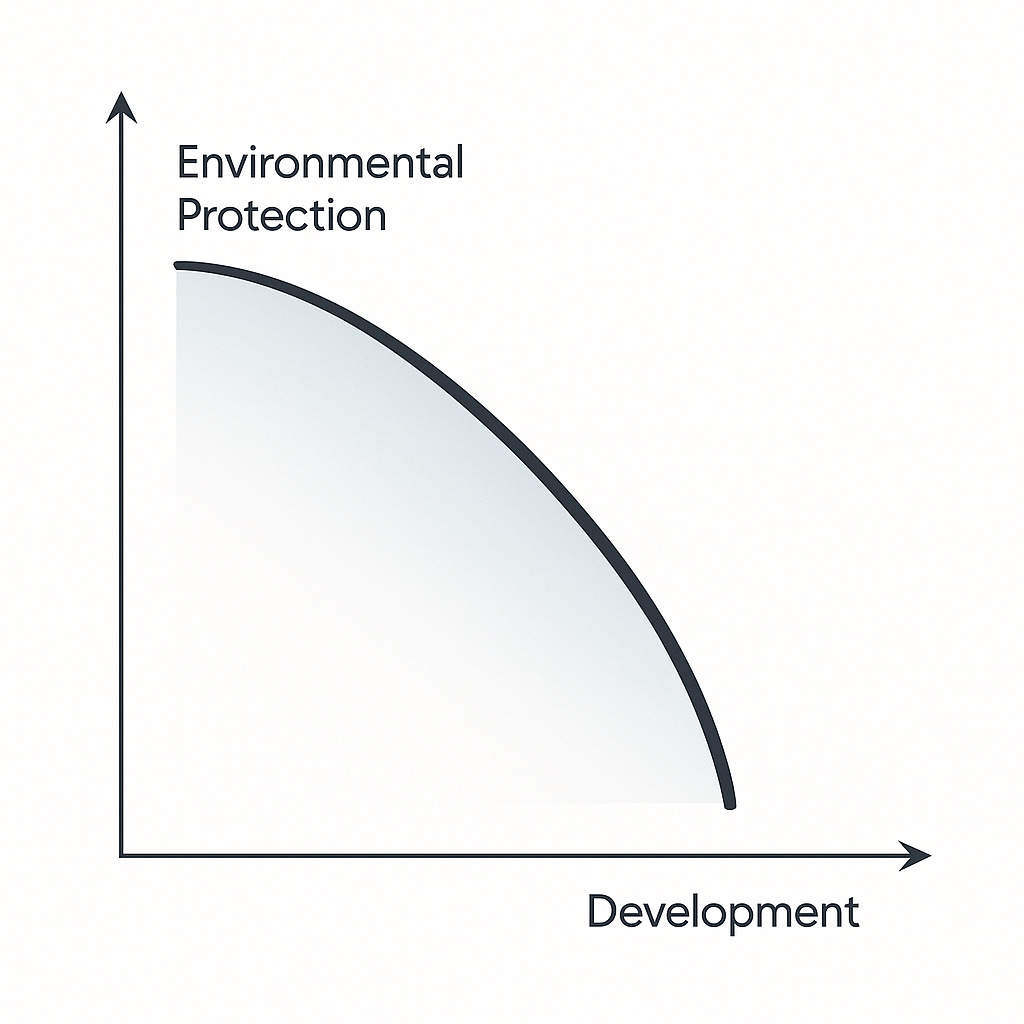

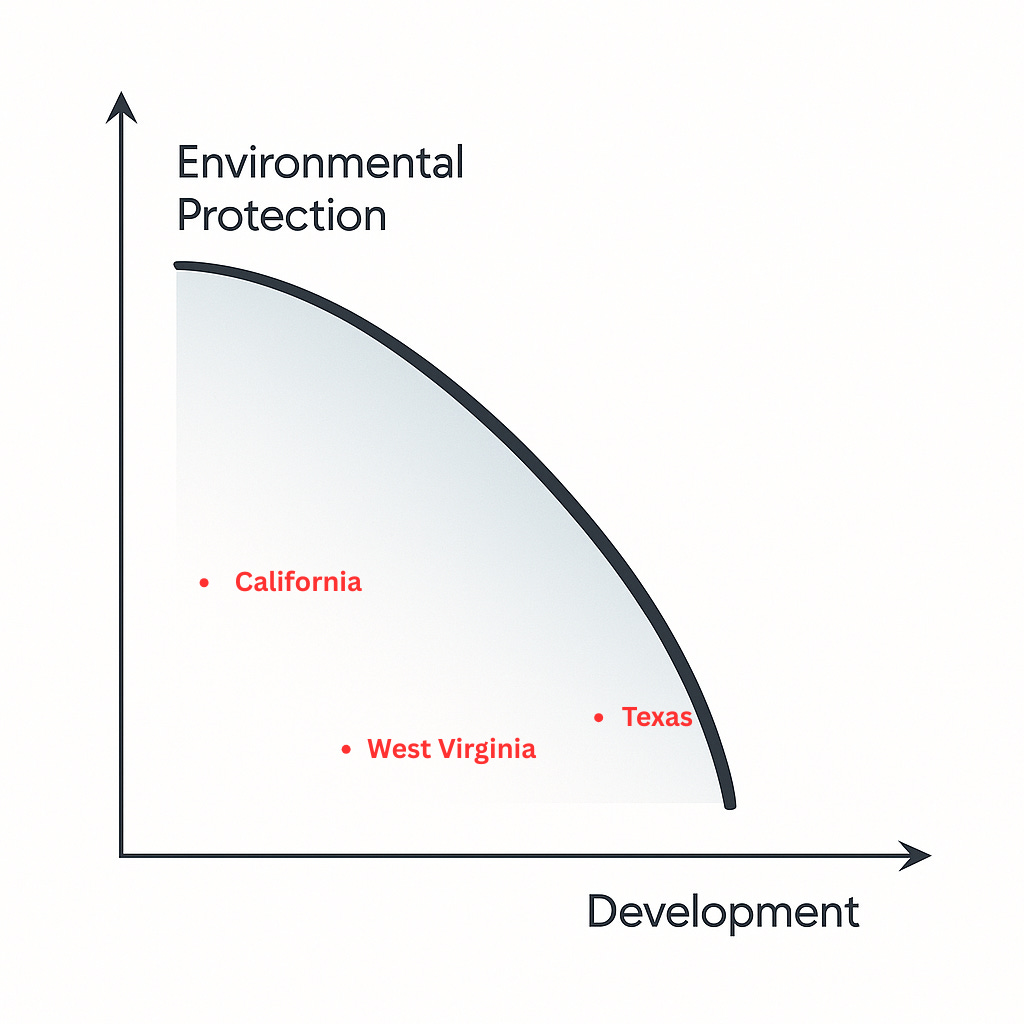

Fortunately, unlike federal permitting policy, which requires a one-size-fits-all approach, states can tailor their policies to their environment. I find it useful to think about the tradeoffs states have to make in terms of a Pareto curve. A Pareto curve is a simple concept from economics that shows the tradeoff between competing objectives, in this case, between environmental protection and development.

The concept is simple. At the frontier (the curve), for a given level of environmental protection, you expect to receive a given level of development. This tracks intuition. The more restrictions you place on development, the harder it gets to develop anything. Builders are less likely to build in places where there are more hoops to jump through. On one end of the curve is a California, on the other, a West Virginia.

Where a state places itself on this curve is determined by the answers to a series of fundamentally political questions. Is it acceptable to have higher home heating prices in exchange for not building natural gas pipelines? Should new transmission lines be granted rights of way through state forests? Should farmland be allowed to replace wildlife habitat? The answer to these questions depends on the relative value that voters place on these goals.

Getting to the Frontier

These are hard tradeoffs that require careful consideration, but fortunately—as I alluded to above—very few of them must be made right now. In reality, there is maybe one state (Texas) that is anywhere close to the frontier of efficiency. Most states are so far away from effectively managing their regulatory systems that both development and protection can be substantially improved with minimal environmental sacrifice.

For example, very few states usefully track their permits online. Most are decentralized, with each agency hosting its own portal. These portals rarely take into account permitting office capacity, break down the review process into useful steps, or label which party is responsible for which part of the process. I have only come across two that take into account the relevant information and incentives, Virginia and Pennsylvania, and both have reported staggering improvements in their turnaround times. In Virginia’s case, they cut their state permit processing time across the board by 65 percent.

And a permitting dashboard is just the tip of the iceberg.

Care about endangered species? Rather than a consultation process, why not survey industrial corridors to determine which areas should be off-limits and fast-track the rest. Ditto for flood zones and wetlands.

Worried about manufacturing plants skirting emissions limits through use of exemptions? Just place a cap on the entire facility, and use satellites and ambient air monitoring networks to track compliance.

Concerned about illegal water withdrawals or irrigation overuse? Equip canals and wells with flow sensors, and you can track violators in real time. Management technologies have progressed enormously since these state statutes were originally passed, and it is long past time we updated their implementation for the 21st century.

Below, you will find a list of the 7 changes that—in my opinion—have the best cost-benefit tradeoff for improving the process of permitting. The recommendations fit into one of two buckets, the first for capitalizing costs (1-4) and the second for scaling the system up and down (5-7). Both buckets have become feasible because of the massive improvements in information management and monitoring technology over the last 50 years.

Data Centralization (Permitting Portals)

This is the big one. The single most important state-level permitting issue is that permits are tracked incredibly poorly. A great deal of the confusion about permitting is downstream of poor data quality. Very rarely do states know which permits are holding up the system, which steps in those permits are the most burdensome, whether it’s the applicant or the office delaying issuance, etc. Unfortunately, not any tracking system will do. To be effective, the tool needs to align the incentives of the agency officials, the applicant, and the state legislators. This is trickier than it sounds. Fortunately, our new guide shows just how to set up such a platform.

Group Permits: General Permits, Permit-by-Rule, and Registration Permits

General permits, permit-by-rule, and registration permits all fall under a bucket I call “group permits.” The details differ, but group permits all bundle similar activities and review them in advance before providing a streamlined application process. They have three big benefits. First, for those more concerned about environmental impacts, group permits can economically justify substantially more up front study than could be done on a permit-by-permit basis. Second, by providing clear requirements, group permits provide certainty to businesses. Lastly, they are dramatically faster to process. A list of common group permits can be found in the FAI State Permitting Report at permittingscorecard.com.

GIS mapping improvements

GIS (Geographic Information System) mapping improvements are likewise about taking advantage of fixed costs (from recently available, more costly, technologies) to reduce the marginal review time of each individual permit. Instead of running an endangered species survey for each permit, states can run a large, occasionally updated survey highlighting high- and low-risk areas with automatic or expedited approval. The critical habitat is kept safe, and private actors know in advance where they can build. Same goes for stormwater drainage, wetlands, floodplains, historic preservation, and rights-of-way, among others. These are costly systems to set up, but can often be justified by the downstream savings.

Cap Permits: Plantwide Applicability Limit Improvements and Flexible Permits

Cap permits such as plantwide applicability limits (PALs) and flexible permits (see Texas’s model) provide hard limits on the outputs that states care about while allowing flexibility in compliance methods. Plantwide applicability limits have this structure for the Clean Air Act, some Clean Water Act discharge permits do as well, as do incidental take permits (endangered species), safe drinking water maximum contaminant levels, fishery permits, green-house gas cap programs, and some hazardous waste permits. These cap permits recognize that technologies and methods of control will change over time, and that businesses should be allowed to meet their obligations in the most cost-effective manner. Unfortunately, many cap permits have shifting, federally-required renewal calculations, which remove some of the certainty for businesses. To the extent that states are able to, they should push to provide certainty about recalculation metrics in advance.

Permitting Staff Funding Mechanisms

One of the most common issues with permit approvals is that staff capacity—if it ever comes online—substantially lags increases in permitting demand. In the good scenario, the permitting department is funded by fees that are connected to permit applications. However, even then the hiring and training of extra officials can take months or years. This causes departments to underhire out of fear of future layoffs. And that’s the good outcome. More often, departments are funded by general appropriations, which require waiting for a new appropriations cycle to even start the funding process. Proper funding is a difficult balance to get right, but an ideal system should have a heavy core of baseline appropriations, supplemented by fees-for-service and an auction/performance mechanism with a limited number of fast-track slots—ideally all with retention authority. This preserves the core of expertise while allowing for slower shifts up and down over time, with sharp spikes in capacity if it becomes worthwhile, as evidenced by the auction mechanism.

Third-Party and Self-Certification

Another option to alleviate the burden of cyclical permitting demand is to allow for third party or self-certification. Under that system, instead of working directly with the agency, the state or agency sets a neutral standard. Individuals who meet that standard (usually some certification training requirement), can be contracted on the company’s dime to perform the analysis that the state otherwise would. Then, the state simply approves, denies, or requests more information on the submission. A number of states have passed third-party or self-certification legislation, with Tennessee’s being the best in my opinion. The incentives here can be difficult, so certification and conflict-of-interest (or insurance) requirements are critical, as well as a hard appealable deadline on the reviewing agency.

Small Tweaks: Parallel Reviews, Single Intake Portals, and Standardized Templates

Parallel reviews are what they sound like. To the extent possible, agencies should coordinate on permits to maximize throughput. If an NPDES permit, a Title V permit, and a wetlands permit are all required, or, more commonly, if multiple separate agencies are required to act on the same permit, these reviews should be conducted simultaneously wherever possible. A single intake portal for environmental permits reduces confusion for applicants by letting them know exactly where to go. Standardized templates likewise reduce confusion for both the applicant and the reviewer by reducing turnaround time. These three may not be the most complicated reforms, but they fix some of the most common pain points for applicants.

Conclusion

Where once it would have been borderline impossible to contemplate a centralized dashboard or parallel departmental review, technology now allows us to solve these coordination issues. Even more than that, it lets us solve them cost-effectively. Now it’s up to us to build them.