The Accidental Architecture of NEPA

Or, More Simply, Why Does it Work that Way?

One of the well-commented-on oddities of environmental law is that the National Environmental Policy Act, the most litigated environmental statute in America, contains no provision for private litigation. A brief overview confirms this. Section 101 declares a national policy of preservation. Section 102 of the act directs federal agencies to prepare detailed environmental impact statements. But nowhere does the statute mention courts, private attorneys general, or judicial review. Nor is there any indication that the members of Congress who passed NEPA understood it to create private standing. When President Nixon signed the act on January 1, 1970, there was no doctrine by which a conservation group would have standing to haul an agency into federal court for failing to study the environmental consequences of its decisions.

And yet—within months—such suits became routine. More importantly, such suits were almost instantaneously afforded deference by the courts. This raises the question: How? How did doctrine change so suddenly to allow for previously uncognizable (e.g. environmental) injuries to provide not only standing but injunctions against government action?

The conventional answer is the Administrative Procedure Act, which permits persons “adversely affected or aggrieved” by agency action to seek judicial review. But the APA was passed in 1946, and for 24 years, environmental plaintiffs were not seen to be “aggrieved” by agency action. Before 1970, standing doctrine required what is referred to as a “legal interest”—a right that was recognized at common law or in statute. Back then, if an organization wanted to stop a ski resort being built to protect the natural beauty of the area, it faced a problem: no law gave it the right to enjoy said beauty. If you wanted to challenge such an act, you needed to win an election.

However, this standard was transformed in March 1970, when Justice William O. Douglas announced in Association of Data Processing Service Organizations v. Camp that standing required not a legal interest but an “injury in fact, economic or otherwise.” That case, aside from being a mess that the Court would spend decades cabining, was the doctrinal key that unlocked NEPA litigation. It turned out that fitting an injury underneath the category “otherwise” was not overly difficult.

But where did Douglas find this formula? In keeping with the rest of his jurisprudence, the opinion offers little by way of explanation. However, in his opinion, he did cite two circuit court decisions from the mid-1960s for the proposition that standing could rest on “aesthetic, conservational, and recreational” values. The cases were Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. Federal Power Commission, decided by the Second Circuit in December 1965, and Office of Communication of United Church of Christ v. FCC, decided by the D.C. Circuit in March 1966.

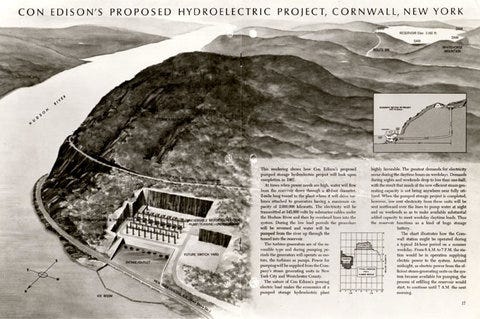

Scenic Hudson concerned Consolidated Edison’s plan to build a pumped-storage hydroelectric power plant along the Hudson River. The at-the-time recently-formed Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference sought to challenge the Federal Power Commission’s licensing decision under the Federal Power Act. Following decades of precedent, the Commission denied them standing. The Commission stated flatly that the conference had no cognizable injury: they had no economic stake, no property rights, no competitive injury. They were merely citizens who liked mountains. In a surprising about-face, the Second Circuit disagreed. Writing for a unanimous panel, the court held that the statutory reference to “recreational purposes” implied that parties who had “exhibited a special interest” in aesthetic and conservational values could qualify as “aggrieved” under the Federal Power Act. It is hard to overstate how substantial of an expansion of standing this was beyond its traditionally understood remit. Prior to Scenic Hudson, your claimed interest had to fall within one of a handful of formalistic, legally protected categories. Afterward, you simply had to enjoy looking at a mountain.

The opinion also contained a procedural innovation. The court found the Commission’s environmental analysis deficient and remanded for further proceedings, with an implicit threat of injunctive relief should the agency proceed before completing a record that the court would find adequate. This combination of broadened standing, judicial review of procedural adequacy, and remand for record development with threat of injunction, contains every building block for what we now think of as NEPA litigation.

Now the story could reasonably end here, but for the second case that supported standing expansion in Data Processing. Three months after Scenic Hudson came down, D.C. Circuit Judge Warren Burger would extend its logic to broadcast regulation. In United Church of Christ, civil rights organizations challenged the FCC’s renewal of a television license for a Jackson, Mississippi station that had egregiously discriminated against black viewers. The Commission denied them standing: they were neither competitors nor parties with economic interests. In his opinion, Burger cited Scenic Hudson for the proposition that non-economic interests could support standing, then went even further. As the “consumers” of broadcasting, he claimed, the listening public had as much right to participate in license proceedings as passengers had to challenge transit fares. Watching television was all you needed to have a right to participate in licensing proceedings.

The similarity in logic and timing between the two cases appears to have been a consequence of a shared intellectual lineage. Among the few sources cited by both opinions on standing is Louis Jaffe’s 1961 article, Standing to Secure Judicial Review: Private Action. Jaffe was a Harvard professor whose 1961 articles on standing explicitly argued for expanding judicial review to “public actions,” that is to say, suits brought by private parties to ensure governmental compliance with law rather than the vindication of any particular private right. In his article, Jaffe suggested that history shows that the Constitution did not require plaintiffs to show invasion of a personal legal interest to qualify as a case or controversy. It is this principle that both Scenic Hudson and UCC would adopt.

After the two decisions vindicated his framework, Jaffe published a follow-up in 1968 in an attempt to fully legitimize the framework. He called such plaintiffs “non-Hohfeldian,” as in standing outside the traditional framework of legal relations; or, more simply, “ideological.” This broad umbrella included nearly all litigants who wished to sue on the grounds that the government had acted unlawfully. Alongside his own addition of the “zone of interests” test, Douglas ratified the framework in Data Processing, in the process citing both circuit decisions for recognizing non-economic injuries. The deed was done; the “injury in fact” test became constitutional doctrine; and the NEPA scourge began in earnest.1

I would be remiss not to mention one final coincidence. Warren Burger, the author of the United Church of Christ opinion, would be appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1969. The day he took his oath, June 23, 1969, was the exact same day the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Data Processing.